Views: 10

The geological formation outside Melbourne is famous for the fictional disappearance of a school group. But it’s also the site of a very real mass disappearance.

Fonte: What Really Happened at Hanging Rock – VICE

What Really Happened at Hanging Rock

The geological formation outside Melbourne is famous for the fictional disappearance of a school group. But it’s also the site of a very real mass disappearance.

Hanging Rock is a popular tourist spot in central Victoria, about an hour from Melbourne. It’s a moody place—eerie, arresting—made famous by Joan Lindsay’s 1967 book, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and infamous by Peter Weir’s 1975 film of the same name. Every year fans flock to the landmark, attracted by the mystery of Lindsay’s missing schoolgirls. It’s even custom to cry out “Miranda!” at the top of the rock.

Down at the base, you’ll find an “interpretative Discovery Centre” where visitors are enthralled by life-sized dioramas and video displays about the schoolgirls who mysteriously disappeared in Picnic at Hanging Rock. Of course, none of it ever happened. No matter how ambiguous Lindsay was about the origins of her story, there were never any schoolgirls who vanished at Hanging Rock.

Yet amidst the obsessive retelling of a fictional disappearance, there’s hardly a mention of the area’s Aboriginal people, nor of their very real removal and displacement. It barely rates a mention.

Of course, Hanging Rock is just one landmark in the vastness of Australia where history seems to begin only after 1770. But it’s not for lack of interest in stories about the land. We are obsessed with lost-in-the-bush stories, as long as the hero is white. The lost Duff children in Western Victoria, the White Woman of Gippsland, even the tragedy of Azaria Chamberlain. These are all stories told repetitively and remembered. But when do we remember, retell, and mourn frontier slaughters of the original landowners, or the lives of stolen Aboriginal children? It just doesn’t happen.

It’s a phenomenon cultural theorist Elspeth Tilley explains as “white vanishing.” She notes “how good non-Aboriginal Australians are at memorialising their own sufferings.” For millennia though, Aboriginal history was passed down from generation to generation in an oral tradition—stories told and remembered, rather than written down. The problem is that when the people disappeared, so too did their stories. The absence of visible Aboriginal history at Hanging Rock doesn’t mean there’s no story to tell. Rather it’s evidence of a violent and destructive wave of colonisation that passed through the region.

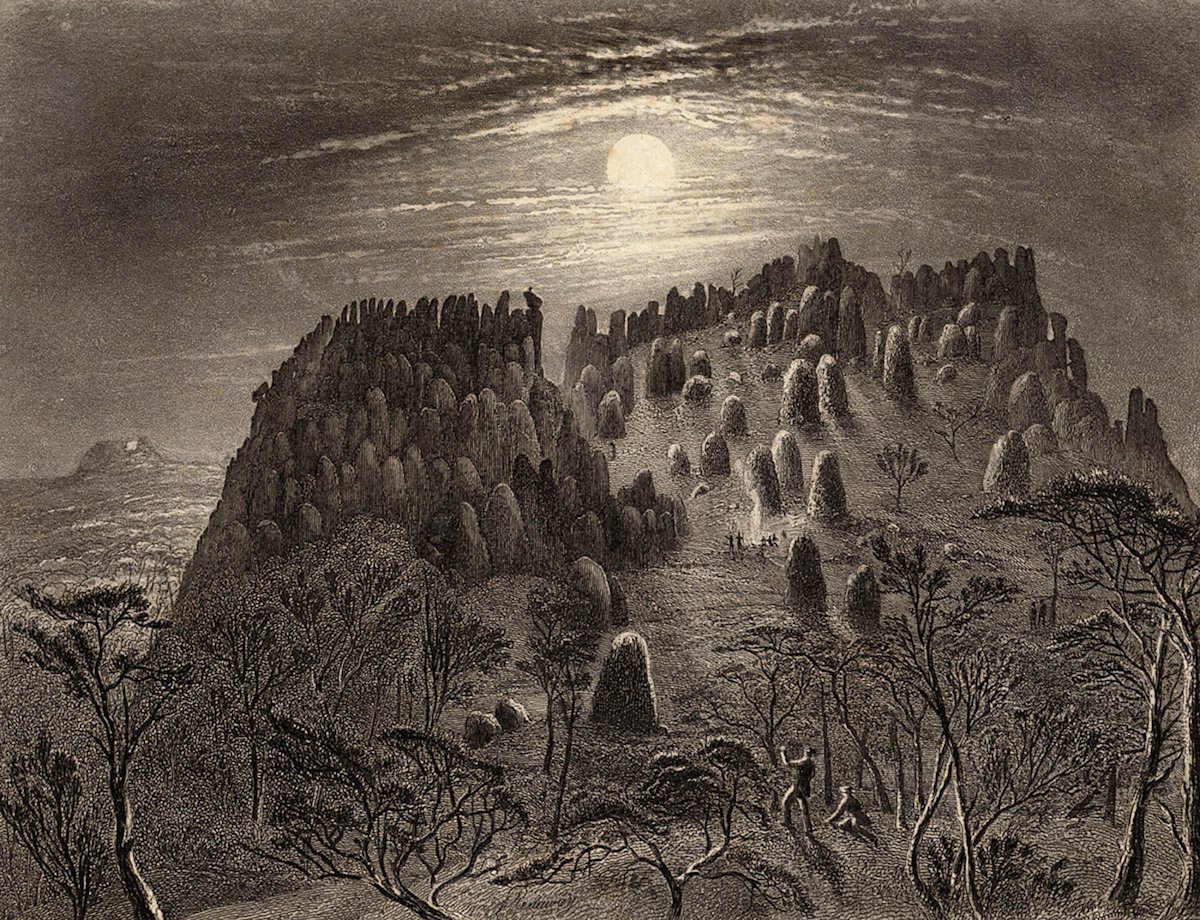

Etchings by the German zoologist William Blandowski, made during his 1850s expeditions into central Victoria. He was one of the first Europeans to describe Hanging Rock, as it’s now known.

From what we do know, the traditional owners have lived around Hanging Rock for more than 26,000 years. It’s believed the Rock was an important inter-tribal ceremonial meeting place, and a significant landmark on the boundary of three different groups—the Wurundjeri, Taungurong, and Djadja Wurrung.

Yet attempts to uncover Hanging Rock’s Aboriginal name have proven difficult. Some think it is “Anneyelong” because of an inscription underneath an engraving of the rock made by German naturalist, William Blandowski, during an expedition in 1855-56. Historian and toponymist Ian D. Clark believes Blandowski misheard the name, and the word was possibly “Ngannelong” or something similar. The evidence does tell us that when Europeans settled the region, huge numbers of Hanging Rock’s Aboriginal population died and were forcibly removed from their land. Many suffered from introduced diseases, such as outbreaks of smallpox. Then in 1863, the Aboriginal people who survived disease and conflict with settlers were rounded up and relocated to the Coranderrk Aboriginal Reserve in Healesville.

Visitors barely register this information at the Hanging Rock interpretative Discovery Centre. But they do read all about how three schoolgirls from Appleyard College and their governess vanished from the summit of the rock on Valentine’s Day in 1900. Hanging Rock, it seems, is haunted by a convenient fiction rather than an uncomfortable fact. On the whole, Australia’s understanding of its own history has been described as a nursery book version, a palatable, whitewashed fairytale that avoids recounting the evident violence and destruction of settler colonialism. We’d prefer to tell comfortable tales of schoolgirls going missing in the bush than face our past. As writer Bruce Pascoe reminds us: the history has not gone away—we just choose not to see it.

Could we do better? When Australians are faced with evidence of absent Aboriginal lives, mass destruction, and lost culture, why do we choose to overlook it? Shouldn’t we acknowledge their loss in potent, affecting panels, artworks, and monuments? Artist Horst Hoheisel’s bold but unrealised proposition for a Holocaust memorial in Berlin provides a powerful anti-monument to absence. Rather than commemorating the destruction of a people via a new construction, Hoheisel proposed instead to blow up the Brandenburg Gate (the symbol of Berlin). “How better to remember a destroyed people,” Hoheisel asked, “than by a destroyed monument?”

Black Lives Matter activists in the US have insisted on honest discussion of the nation’s history—campaigning for the removal of confederate monuments and symbols. And as writer Jeff Sparrow argues, “if black lives really matter in Australia, it’s time we owned up to our history.” Sparrow has called for similar grassroots campaigns to identify and commemorate Australia’s troubling frontier past. These, he says, must involve localised activities aimed at drawing attention to specific histories in specific places, like Hanging Rock.

It’s for these reasons that I started a campaign called Miranda Must Go. Hoheisel was right: the only way to make people fathom loss on a mass scale is by taking away one of own beloved cultural icons. Our addiction to mythic vanishing whites must stop. We need a detox: a moratorium on Miranda. By ditching our obsession with the disappearing schoolgirls of Hanging Rock we can create space in the landscape to remember Aboriginal people, their losses, and incredible survival despite white Australia’s efforts to destroy them for 229 years.

But this is just one campaign in one location. There needs to be hundreds, thousands of others aimed at challenging the white narratives that dominate across Australia. It’s time to let go of our comforting nursery tales and address our past like grown-ups.

You can find out more about #MirandaMustGo and how to get involved here.

Latoya Aroha Rule’s Brother Died in Police Custody: Here’s What She Did Next

The problems facing First Australians don’t end when Invasion Day protesters go home. Here we meet a campaigner making a difference all year round.

In September 2016, Latoya Aroha Rule made a long journey to an South Australian courtroom to meet her big brother as he came out of remand. Wayne “Fella” Morrison had been held for six days without conviction, and was due in court that morning. But Wayne never made it.

His family had to wait over 12 hours to find out why.

Wayne was the kind of guy who liked to take his young daughter fishing at St Kilda beach. He was also a phenomenal artist, and he’d never had any trouble with the law. Yet somehow, at the hands of guards at Yatala Labour Prison, the 29-year-old Wiradjuri and Kokatha man had been left brain dead.

Sitting in that court room, waiting for Wayne to appear, Latoya and her family had no idea what had happened. Only after their pleas for help spread far and wide through Facebook—and the family’s own contacts in the South Australian Aboriginal community—did they discover where Wayne was. He’d been transferred to the Royal Adelaide Hospital where he was in a critical condition.

Three days later, while Wayne was lying in intensive care on life support, Latoya’s family said their goodbyes. Technically he was still on remand, so officers watched on outside his room.

Since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which began in 1987, there have been about 400 Aboriginal deaths behind Australian bars. No prison guard or police officer has ever been charged. But Latoya isn’t going to settle for inaction. She wants to make sure Australia knows the name Wayne “Fella” Morrison, and has began organising national rallies—not just for Fella, but for all Aboriginal people brutalised in custody.

Latoya, a 24-year-old academic, has become a prominent black activist since Wayne’s death. The bloodlines of two strong Indigenous cultures run through Latoya; on her mum’s side she is Wiradjuri, and her father is Maori. As a child, Latoya grew up immersed in another culture too—the Christian church. Her dad was a pastor. “I guess my life was always around Christianity, everyone’s equal and all that shit,” she explains via Skype from her sun-scorched home in Adelaide, an Aboriginal flag suspended behind her.

In the past, Christianity dictated Latoya’s political leanings. She’s open about her old beliefs; telling me she was once “anti-gay” and “super homophobic.” “Everything the church carries, all its morals and values—that’s who I was, believe it or not. I was just fed a whole lot of crap, and I was never critical,” she explains. “I was told not to ask questions. I was always inquisitive, and really driven, but I never asked questions.”

Then came a negotiation of her faith, a realisation that her Wiradjuri and Maori roots were vital to her understanding of herself and the world. “I realised that my dad was purposely distancing me from our culture [growing up]. It was unjust.” For Latoya, reconnecting with her Wiradjuri heritage—silenced throughout her childhood—is now integral. She says she can’t imagine going a day without finding some way to reconnect. But this revitalisation, an important act of resistance, also brings up wounds from the past.

Latoya’s great-grandmother was killed by a white man, who ran her over with his car. The son of a police officer, the man was never charged—a story many other black families are all too familiar with. Some of Latoya’s family have language, songs, and cultural knowledge that her great-grandmother passed down to them. But because of the distance Latoya’s father kept from his culture, she never had a chance to discover hers. But the suffering of her family at the hands of the state was passed down, from generation to generation, and the same injustice of her great-grandmother’s death lingered over her brother’s.

“For me, the grieving process hasn’t really started properly. I was pretty upset initially but then I had to go protest, because we have to enact some justice. I had to look at my brother as another Aboriginal man. You say sure, he was my brother, but he’s also someone else’s brother. This is not just about Wayne, it’s about other people like Ms Dhu. It’s systemic, it’s oppression.”

The preliminary fight began only a couple of months after her brother’s death, when Latoya helped organise a nation-wide call for action, with protests held in Brisbane, Adelaide, and Sydney. Across the three cities, protesters signs calling on justice for “Fella” Morrison as well as for Ms Dhu, the young Yamitji woman who died tragically in a South Hedland watchhouse after being denied appropriate health care, twice.

Now, Latoya’s family will endure the long hard wait to find out what happened to their loved one. They know that they could be waiting for up to two years for a coronial inquest, which often leads to little. In some cases, like in New South Wales, devastated families have been forced to wait up to five years for an inquiry to begin, like the case of Mark Mason snr, who was shot by police officers in Collarenebri in 2010.

There has never been a police or prison officer convicted over an Aboriginal death in custody.

The death of her brother has also had a huge impact on Latoya’s next steps into academia. She is considering looking into the usage of CCTV footage in death in custody cases, as the family await the images of Fella’s last hours.

She says unless the system changes it will remain a “tangible threat to black people’s safety”. “This is one of the ways black people die in this country.” But as the reports continue to stream in about our mob dying behind bars, more and more young Aboriginal people are beginning to stand up. They are attending protests, making sacrifices, and lifting their voices up across the country. There is a recognition that these aren’t anonymous faces behind prison bars. They aren’t unknown names adorning protest banners. They all have brothers and sisters – they all have a Latoya Rule—who are fighting not just for their own, but to dismantle the system that has lead to too many black deaths.

Words by Amy McQuire. You can follow her on Twitter

Photos by Sia Duff

Classic Perth: Let’s Build a Highway Over a 5,000-Year-Old Sacred Site

The Roe 8 protest is Australia’s Standing Rock.

COLIN BARNETT ART BY ASHLEY GOODALL

If Perth has one defining feature, it’s the vast empty spaces between its urban and suburban centres. Forget cramped inner-city life—in Perth, you live in a big house with a big backyard that’s an hour drive away from the CBD along a desolate highway dotted with skimpies bars and high rises. Paradise.

Town planning in Perth has become about connecting suburbs with long stretches of asphalt. This is how the Roe 8 project—a proposed $550 million highway extension connecting the city’s industrial precinct with its coastal one—came to be. Unfortunately, like a lot of public works projects in Western Australia, Roe 8 is expensive, environmentally destructive, and requires demolishing land of spiritual significance to its traditional owners. In this case, the Beeliar Wetlands have been used by the Noongar people for more than 5,000 years.

Concerned citizens have been protesting Roe 8 for months, staging lengthy sit ins and placing their bodies in front of bulldozers. The #Roe8 protests are WA’s version of Standing Rock. And as with the Dakota Pipeline, activists have had little success in changing the government’s mind. Construction of the road has already begun, and a lot of the wetlands are already flattened. But none of this is exactly surprising: Building a highway on a 5,000-year-old sacred site is actually the most Perth thing ever.

NOONGAR PROTESTERS AT THE ROE 8 SITE. IMAGE COURTESY ABORIGINAL HERITAGE WA

“You’ll find there’s been a lot of care taken with some quite small bits of European heritage in Western Australia, but not so much with Aboriginal heritage,” University of Western Australia archaeologist Dr Joe Dortch tells VICE. “It’s certainly very confronting when Aboriginal heritage is treated so badly. Some of us try and acknowledge and record it, but other people seem to think it doesn’t matter.”

He’s right. Perth’s primary tourist attraction is the Bell Tower, an underwhelming blue triangle installed by the Swan River in 1999, which houses several “historic” bells imported from Trafalgar Square, London. Perth isn’t a city that pays tribute to anything other than a colonial past—a massive public foreshore development completed only last year, Elizabeth Quay, was tellingly named after the Queen.

For an archaeologist like Dortch—one who’s understandably more interested in studying artefacts from the oldest living culture on Earth than those from colonialists who docked their tall ships on the Swan River—work can be pretty tough in WA. The state government has long waged war on places of Indigenous cultural significance, literally changing the definition of what constitutes a “sacred site” in order to deregister several of them for mining. “Somewhere between 30 and 80 sacred sites have been taken off the register, and on top of that a grand total of 3,200 other significant sites were taken off the register in recent years. That’s pretty unprecedented,” Dortch says.

But the Beeliar Wetlands isn’t just another archaeological site. In the 1970s, an expansive dig uncovered stone tools and carvings there that were estimated to be as old as the pyramids in Eygpt. The state government has attempted to discredit these findings, or claim that the area has been so disturbed in the decades since that its archaeological value has been lost. Dortch and his colleagues beg to differ. Led by prominent West Australian archaeologist Dr Fiona Hook, the team staged their own renegade exacavations in the Beeliar area to prove its academic and cultural significance. Although they’ve been barred from digging in the Roe 8 corridor, their cursory excavations in the immediate vicinity have revealed more stone tools that Dortch estimates to be at least 5,000 years old.

“There’s nothing certain in archaeology,” he explains. “But the artefacts are made of a certain kind of rock called chert, which is sourced from places that became submerged around 6,000 years ago.”

Dortch stresses the team’s investigation of the area was extremely superficial—but given more access and resources, who knows what else they could have found. He also explains the state government did make its own archaeological investigation of the area, but didn’t try very hard to find anything. “We dug 20 small pits, and found artefacts in six of them, so that’s a one in three chance of getting artefacts. And they were only concentrated in one area,” Dortch says. “They only did one 20 centimetre shovel pit, which doesn’t tell you much at all.”

NOONGAR ELDER CEDRIC JACOBS HOLDS CHERT THAT DORTCH AND HIS TEAM FOUND ON THE SITE.

Of course, to truly understand the special significance of the Roe 8 site, you need to speak to its traditional owners of the land. Beeliar Wetlands custodian and Whadjuk Noongar woman Corina Abraham has worked tirelessly behind the scenes of the Roe 8 protests, even lodging an unsuccessful legal challenge against the WA and federal government under section nine of the Aboriginal Heritage Act. “We’re doing a white man’s fight through the courts, but we’re never going to win as First Nations people,” Abraham says. “When elders were consulted [about Roe 8] back in 2010, sadly, a few of them didn’t even come from this area—and yet they were allowed to make a decision on it.”

The entirety of Perth is technically built on Noongar land, but the Beeliar Wetlands site is of particular significance to Indigenous people. “There are many cultural sites but this is the crucial one, the only one south of the river. The damage that this will do [to our community] is great,” Abraham explains. “Our history there goes back over thousands of years. My ancestors lived and gathered on country around here, and our mythological significance to the area is through our dreaming, our spiritual connection to country. And that’s the important thing. Bibra Lake is the resting area for our Wagyll, so that connects us to the Country as well. And we continue that through our stories and our song lines and in person.”

A ROE 8 PROTEST HELD IN FREMANTLE LAST MONTH. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE SAVE BEELIAR WETLANDS CAMPAIGN

Archaeologists like Dortch are fine with Roe 8 being built in theory—but at bare minimum, they want more time to study the area and archive what they find before the bulldozers come and destroy everything. But the area’s Indigenous owners want the destruction stopped altogether, and you can’t blame them. The Beeliar site is old, but it’s also still being actively used by Noongar family communities in the present day.

“It’s a birthing area for women, it’s a men’s area, it’s an area where many clans congregated for corroborees, it’s an area where ceremonial gatherings have occurred over thousands of years,” Abraham explains emphatically. “This area is as significant to us as what a church is to Catholics or any other religion. It’s our church, it’s who we are, it’s where we come from.”

For many Noongar people, Roe 8 feels like the final straw. “It gets devastating, it stresses me out every time I drive out there and see the desecration of our country. What was left of our cultural heritage after colonisation, you know?” says Abraham. “It’s about maintaining what we have left, the unique bushland that only grows here. That’s unique to us as West Australians.”

According to polls, WA’s Liberal government is going to lose an election this month. If they do, the incoming Labor party has promised to scrap the Roe 8 project altogether. Whoever wins Government, both archaeologists and traditional owners want the heritage area investigated and preserved. If this doesn’t happen, a little more of the uniqueness that Abraham talks about will have slipped away forever—in a pattern of destruction that, ironically, makes Perth pretty distinctive.

Follow Kat on Twitter